Hello. In this video, we’re going to consider an important configuration option, which is important to consider when designing wireless networks. And that is which frequency band are we going to advertise each SSID in? Now, mixed access points as we know, have a dual radio access points. They have 2.4 and 5 gigahertz radios. And when we configure an SSID, as I’m doing here in the mixed UI, I have three options. I can have that SSID available in the 2.4 and 5 gigahertz frequency band, just in 2.4 gigahertz, or just in 5 gigahertz. Now, I think the traditional approach to wireless LANs was always to advertise SSIDs in both the 2.4 and the five gigahertz band.

By doing it, we ensure that any devices which could only connect on 2.4 gigahertz, they can connect using the 2.4 gigahertz radio. And if we have clients which can do both 2.4 and five gig, they can connect on either frequency they choose. Now, while this approach seems to provide the most flexibility, it does open up some problems. And that is that the 2.4 gigahertz band is often very, very congested. We only have three merely available non-overlapping channels we can use in that band. And most enterprise deployments have more than three access points, so we have to have access points on the same channel. Often introducing co-channel contention. We also have to consider neighboring access points we can hear. And very often in a 2.4 gigahertz environment, you are going to see 4, 5, 6 axis points all on the same channel. All contending for and congesting that frequency band.

The other thing about a 2.4 gigahertz band is it’s a license free frequency band pretty much, much globally and has been for some time. So therefore, other technologies apart from wifi use the band. We’ll often see wireless’s video cameras in this band, baby monitors, cordless phones, PRI motion sensors all transmitting in this band. So it’s not only congested from wifi, but it also has a lot of interference sources. The five gigahertz band on the other hand, is often a lot less congested. We have a lot more non overlapping channels, less interfere in sources, and as a result our wireless LAN performance is very often twice, if not more times better in the five gigahertz band than the 2.4 gig band. Therefore, what I want to do is ideally I would rather my clients were using the five gigahertz band than the 2.4 gig.

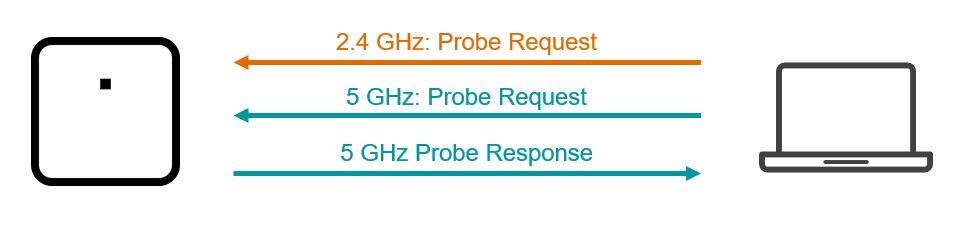

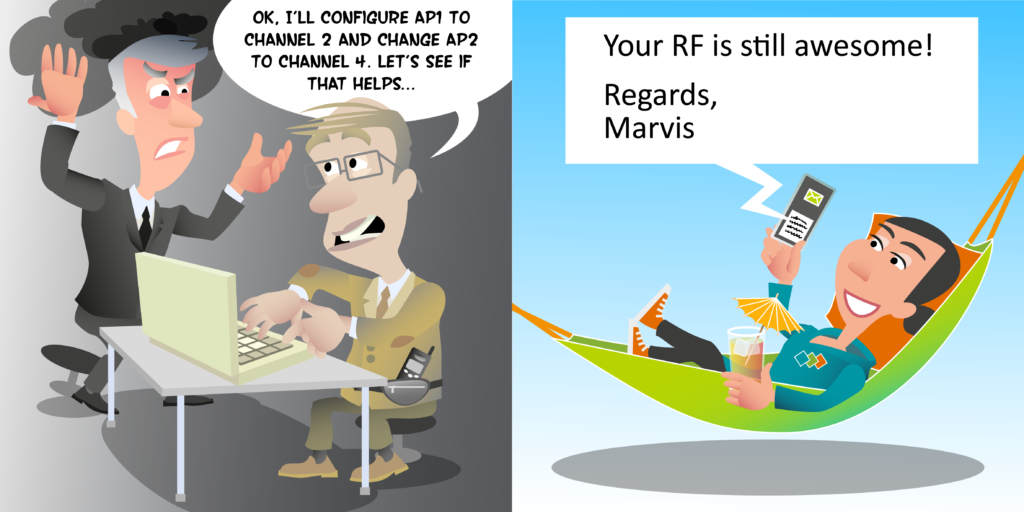

But the problem with this is it’s the clients who make the choice. And as an administrator as much as I may want them to, if I give them the option of 2.4 and five gig, they may well connect on 2.4. Now, I can do things to try and encourage clients to connect that five gig. I could make the five gig radius 60 be stronger than the 2.4 to try and encourage them to connect to the stronger signal. Mixed also supports a band sharing option. What band sharing does is it basically tries to encourage my clients to connect on the five gigahertz band once it’s determined that a client can support both bands.

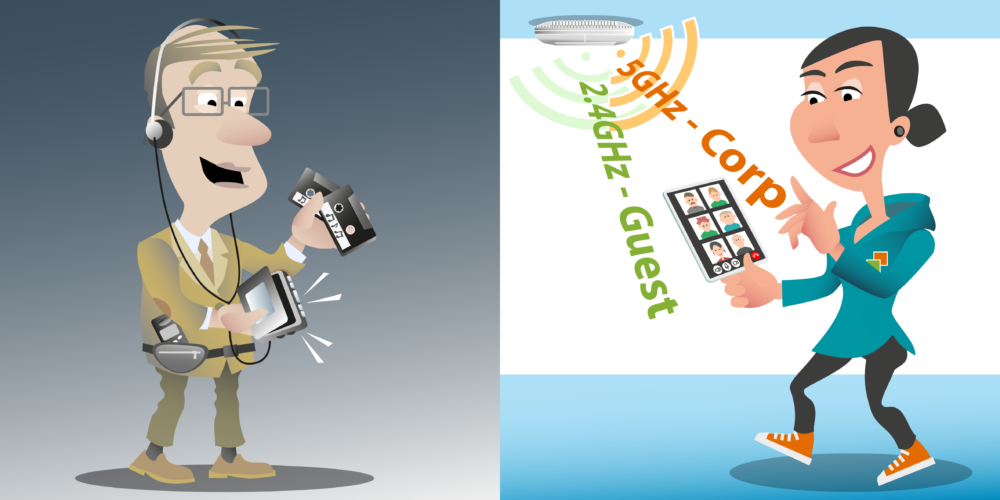

But it is just an encouragement. Clients may ignore that encouragement and connect on 2.4 anyway. In fact, many do. So while band sharing will help, it’s never going to guarantee all clients that can do five gig, will connect at five gig. So what’s your option? Well, I’m a big believer in not using this option, not having the same SSID advertise on both bands. And putting different SSIDs on different frequency bands. So for example, here if I’m configuring a corporate SSID I would rather make it five gigahertz only.

If I make it five gigahertz only, all clients have to connect on five gig or not connect at all. So I’m guaranteeing 100% of my users are going to be on the better performing, far less congested five gigahertz band. Now, of course, when we suggest this option to customers sometimes they will say, “Well, what if we’ve got 2.4 gig only devices?” The truth of the matter is that’s not often the case on a corporate network. Corporate network are generally for corporate provision devices, laptops, smartphone, tablets, which have been provisioned by the business. Who will often replace these devices, laptops every five years, smartphones may be a two years. To have a 2.4 gig only device, you’re probably talking about a 10 plus years old device.

So for traditional office corporate environments, this is normally a good idea. Especially, if we want to support lots of voice and video conferencing, and high density, and data rate requirements. Now, in some environments we will have to support 2.4 gig only devices. Let’s consider warehouses, which maybe buy barcode scanners and keep them for 20 plus years. So if they’ve got an old barcode scanners, then maybe support the 2.4 gig only network. We’ll set up a barcode scanner SSID2. A 2.4 gig only SSID for those devices. If we’re supporting IOT devices, again a lot of those might be 2.4 gig only when we set up a network just for those devices. Guest networks, BYOD networks may want to be 2.4 gig because we may have devices such as smart watches, which some may be 2.4 gig only capable.

But when we come to the corporate network, I’m a big believer in trying to keep it five gig only. Now again, some companies may have concerns there’s a 2.4 gig only corporate device out there. Well, in these scenarios I would say, let’s also set up… Let’s have the main corporate SSID is five gigahertz only. But we could set up a corporate SSID on the 2.4 gig only band as well. This might be called Corporate Legacy to support legacy older devices. And therefore, if one of these devices when we make our five gig only network available, phones up the help desk and say I can’t connect. The conversation could go a little bit like this. “Do you have an older legacy device?” “Oh, I do actually. It’s an old iPhone four.” “Well, do you see the network Corporate Legacy? We’ve made a provision, you can connect to that network.” And they’ll get the same 2.4 gig only performance they’ve been getting previously with that device. It just means everyone who has a five gigahertz capable device will definitely be connecting five gigahertz and getting a much better performance.

Thank you for watching and goodbye, for now.